Each week, Dana White walks into the chief kitchen next to his office to eat some grotesquerie dreamt up by his chefs. Today they present the Ultimate Fighting Championship chief with a “doughnut grilled cheese”. This was prepared by slicing a glazed doughnut in half, buttering either side, putting a slice of American cheese in the center and sautéing it. White is worked up by the culinary creativity but, after one bite, he shakes his bald head into his social media guy’s phone and says: “I don’t adore it. One and done. No bueno.”

Several employees in the chief kitchen beg him to reconsider. White’s enormous bouncer body resists any halt in forward momentum, but he manages to remain put. He loves these chefs, great guys, so sure, OK, another try. The chefs fry him a more energizing, hotter, meltier grilled cheese doughnut. White bites into the brand new one and agrees it’s higher. But he tells the social media guy to post the “no bueno” video. It’s Fuck It Friday, not Nuanced Deliberation Friday.

There’s no other president of a sports league who’s the face of his brand like White is. No network is attempting to get Premier League CEO Richard Masters to host a reality show but, in accordance with White, the Food Network has signed up for eight episodes of Fuck It Friday. White’s already a TV star, having hosted The Ultimate Fighter, a reality show that now airs on BT Sport, ESPN+ and Hulu, since 2005. It’s so popular it’s accompanied by Dana White’s Contender Series, during which he looks for even less seasoned fighters to recruit.

Over the past 20 years, White built the UFC right into a $4bn company that made greater than $1bn in revenue previously yr. The corporate has a seven-year cope with ESPN that landed it $1.5bn, before lucrative pay-per-view rights. In March, the UFC sold out London’s O2 arena with a $4.3mn gate, the venue’s record for a sporting event, then topped it again in July. This Saturday, after winning a decades-long battle to make mixed martial arts (MMA) events legal in France, White will host his first event in Paris.

Unlike most corporate leaders, he did all of this by cursing at press conferences, threatening adversaries and publicly trashing the weaknesses of his staff, the fighters.

It could appear to be White, 53, is the beneficiary of a world that’s turn out to be more crude, more combative, more individualistic, more honest. A world where honour culture is ascendant. A world where Oscar winners slap presenters on live TV, the richest person on the earth challenges the president of Russia to a fight and strongmen have taken over countries from El Salvador to Hungary and the Philippines. A world becoming increasingly like him each day.

That shouldn’t be what happened.

What happened was that White made the world more like him. He did this not by ordering around employees and imposing his will. He did it through enthusiasm. That is White’s great talent. He can transfer his immense excitement to others with almost no lack of energy. “Even pre-UFC, anything Dana did or bought, he could persuade you it’s the best thing on the earth. To him it’s. He’s not manipulating you. After they were in Greece, I asked, ‘How was it?’ and he went on this tirade about the way it’s the very best place he’s ever been and ate the very best chicken he ever had. It may very well be an auto body shop in LA. It’s the whole lot,” says his younger sister Kelly. It’s not a sales technique he activates and off. “He’s 100 per cent like that each one the time.”

When Dwayne Johnson flew to Minneapolis years ago to look at a UFC fight, White asked The Rock why he wasn’t on social media. “I used to be saying, ‘I don’t see the worth. I see people tweeting about what sort of hamburger they’d.’ Dana turned to me and said, ‘You may have got to have interaction in social media. It is going to be one in all the best things for your enterprise.’ And I began to laugh because he was so serious.” White insisted Johnson meet his social media consultant. “Ten years later, I’m, fortunately, the most-followed American man on the earth,” Johnson says.

Dana White in his office in Las Vegas, which can also be home to a few of his favourite artworks. Albert Watson’s portrait of the boxer Mike Tyson (Catskills, NY, 1986) is on display behind him © Holly Andres

Around the identical time, White convinced me it was key to my writing profession, and my life, to have a Muay Thai trainer kick me, which taught me the priceless lesson that being kicked within the leg by knowledgeable leg kicker hurts. I regretted it immediately. Yet just a few hours later, he convinced me to let former UFC fighter John Lewis choke me out until I used to be unconscious. Twice.

Now he’s pumped to point out me a stare-down, the pre-fight ritual where UFC combatants stand inches away from one another and make tough faces for the cameras like they’re Nineteen Eighties cologne models. It looks like a vestigial, fist-shaking marketing stunt from a pre-television era. But White tells me it’s his second-favourite a part of fight week, after the fight itself, which is an enormous statement because he has so many favourite parts. And this time can be even higher, if that’s possible, because he gets to see me experience it for the primary time.

So I’m following White through a crowd, past security guards, up on to the stage of the theatre within the Park MGM hotel in Las Vegas. We head to centre stage, in front of ring card girls in Monster Energy drink-branded bikinis and tiny belts that aren’t holding anything up. Soon, I’m just a few inches between the faces of shirtless UFC featherweight champion Alexander Volkanovski and his shirtless opponent, Brian Ortega. “How cool is that this?” White asks, in a way that shouldn’t be in any respect an issue. And it’s indeed very cool.

From here, I can see that the stare-down isn’t performative. Volkanovski and Ortega are scanning for weakness. They provoke reactions in one another so as to add to their data dumps. Sometimes the algorithms demand much more information and fighters start punching one another, which White is worked up might occur here.

Volkanovski has been insulting Ortega since they were guest coaches on The Ultimate Fighter. Which is why White thinks that show is so significantly better than The Real Housewives. “You see all these reality shows, but you never get to see them fight,” he says to me, as if dissecting story problems in a script. But as much as he would personally enjoy it, he doesn’t want these two guys to fight straight away, because they may get hurt and cancel the event they’re promoting. Plus, not stopping fighters from going at it outside regulated bouts is unprofessional. It happened every week before at a weigh-in for a Showtime boxing match, which White cites as one other example of how boxing has devolved: “I’ve been shitting on Showtime all week. I’d higher not fuck this one up.”

It looks like he might. As cameras flash, Volkanovski taunts Ortega. “You look slightly nervous. You look slightly shook,” he says. Ortega, his camouflage baseball hat on backwards, shakes his head, no, he’s not nervous. But his eyes look crazed attributable to days of near-dehydration to make his weight class, so when he feints towards Volkanovski to point out he’s not scared, the tattoo of a hissing serpent that runs down Volkanovski’s arm pops, and I jump backwards.

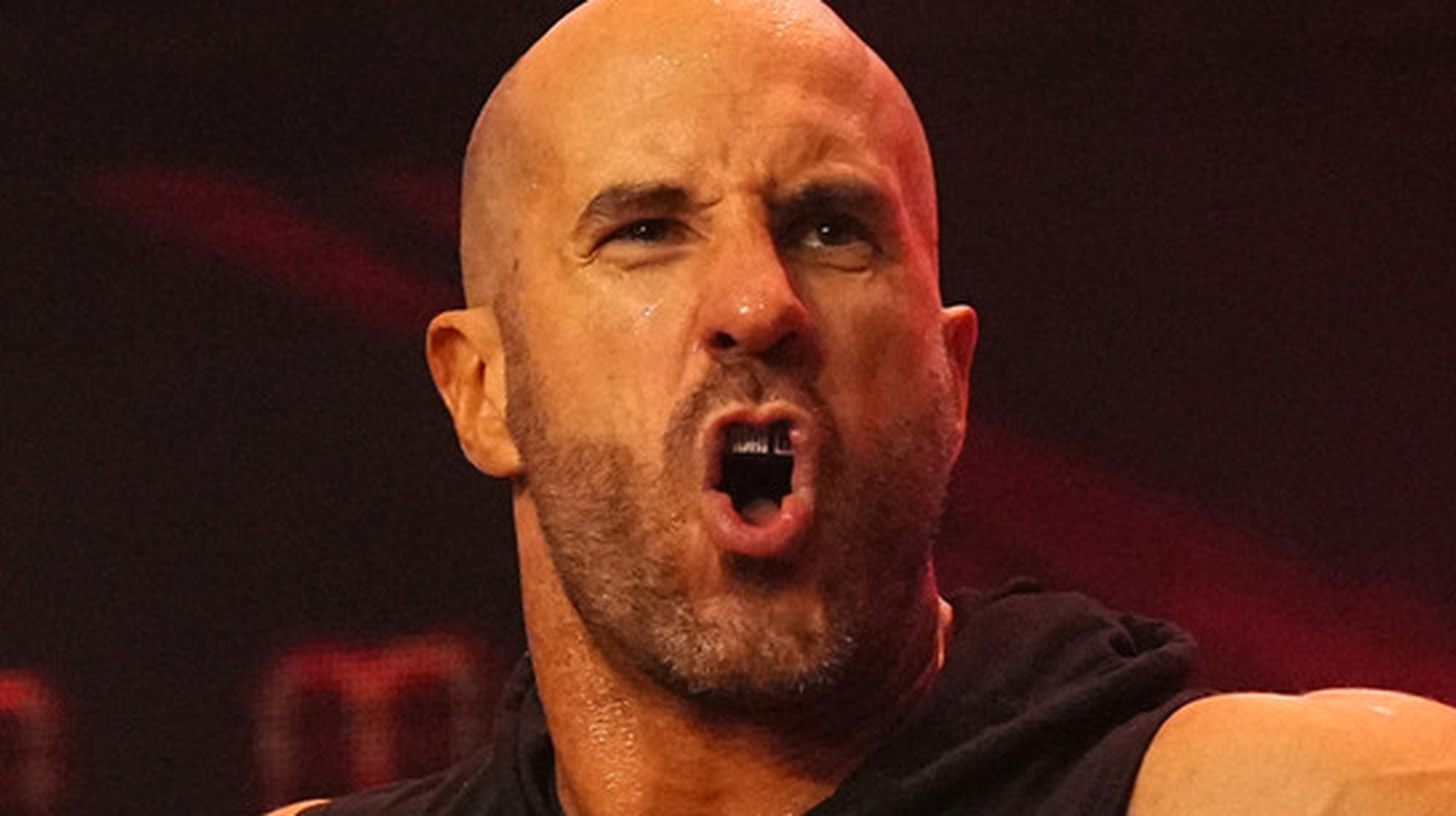

White with Alexander Volkanovski (left) and Brian Ortega at their weigh-in on the Park MGM in September 2021. White first took on the UFC when politicians and the AMA were attempting to ban it © Chris Unger/Zuffa LLC/Getty Images

White leans in. “I’m slightly nervous. I’m slightly shook,” he says to the fighters, laughing. He gently separates them together with his thick arms. He pats me on the shoulder, thrilled for my luck at witnessing this alpha flexing. And I do feel lucky. All of the animosity that’s muted and suppressed in other sports is alive here. White has all the time loved fighting. He’s all the time believed everyone loves fighting. His job was merely to remind them. Which, in 2001, when White took over a failing area of interest spectacle, seemed utterly idiotic.

After I was in elementary school, my dad, who boxed in college and in the military, would watch fights on Friday nights. I hated them. I couldn’t comprehend how such barbarism was still permitted in a society so civilised that I played video games as an alternative of getting my clothes dirty playing sports. I used to be proven right. After Mike Tyson bit Evander Holyfield’s ear in 1997, boxing became too barbaric for the mainstream. In a 2006 Gallup poll, only 2 per cent of Americans named boxing as their favourite sport, fewer than picked figure skating.

Unlike me, White believed that boxing had a business problem, not a cultural one. People in every a part of the world, he says, still stop whatever they’re doing any time a fight breaks out to look at. Admiring someone who can beat another person up is built into our DNA, he insists. Which is why White believed mixed martial arts (MMA) could be popular in every country. There are not any rules to learn, no history to understand. “The UFC is like Andy Warhol. Cricket is Mark Rothko. Everybody gets Andy Warhol. With Rothko, the entrée is so hard,” says Lawrence Epstein, UFC’s chief operating officer. A former lawyer, Epstein met White when he took his boxing workout class within the Nineteen Nineties.

At the same time as White was teaching Las Vegans to jab and cross, he believed fighting would make a comeback. He says there are three foremost kinds of people on the earth: nerds, jocks and stoners, none of whom truly understand the others. There’s also a small fourth group: fighters. They’re outsiders who lack social skills and operate on a base level. As a child, he thought he could be one.

White was born in 1969 to a 19-year-old high-school dropout mom, who alleges her parents abused her, and a 21-year-old alcoholic dad. In her 2011 book, Dana White, King of MMA, June White describes her life as a teen this manner: “Most of my acquaintances were a rogues’ gallery of gangsters, bank robbers, drug dealers . . . and gunrunners.” By the point Dana was eight, his dad had left the family.

Dana, in accordance with his mom’s book, mostly excelled in getting in fights. Though that could be the creator’s skewed perspective, because Dana’s fights are the accomplishments during which she expresses essentially the most maternal pride. In her account, he’s all the time defending a girl’s popularity, his family name or a weaker victim. Ancient Romans were raised in less of an honour culture than Dana White.

After highschool, White worked as a road paver, a bouncer, a hotel bellman and, eventually, became an apprentice boxing trainer in Boston. That’s when he met real fighters and realised he wasn’t one in all them. He says he never looks at any UFC fighter and thinks he could take them: “Not even the women.” White realised he was a jock. And, as countless movies have proved, jocks stop having a transparent path after highschool. White also learnt he wasn’t even a troublesome jock. When Whitey Bulger, the infamous mobster, had his men threaten White for not paying $2,500 in shakedown money at his gym, White hightailed to Nevada. His mom moved back too.

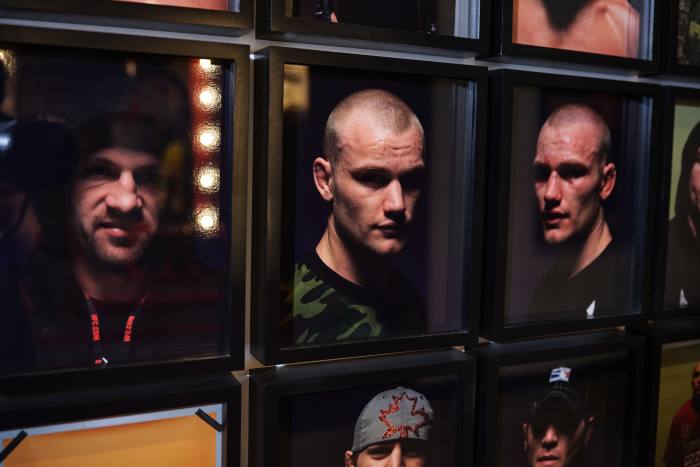

Pre- and post-bout portraits of UFC fighters on the partitions of White’s apartment-sized office, which also incorporates a huge personal gym, a walk-in wardrobe and a sports bar © Holly Andres

In Vegas, White’s boxing class became so popular he taught it in a large gym that’s now the world’s largest strip club. He became an area celebrity and, by 2000, was managing two mixed martial artists who would go on to turn out to be huge stars, Tito Ortiz and Chuck Liddell. White found himself fighting over the payout for a contract he had negotiated for Ortiz with a music promoter who had co-founded the UFC in 1993.

Like kids wondering which superhero would win in a fight, the UFC asked which martial arts discipline would dominate. But it surely wasn’t easy to advertise, which was why the UFC hadn’t paid White’s fighters. White convinced Lorenzo and Frank Fertitta III, brothers he knew from highschool, to purchase the struggling outfit for $2mn. White had trained them and, after meeting a ju-jitsu fighter, all three learnt the discipline. The Fertittas figured it could be a fun side hustle to their hugely successful local casino business. They gave White 10 per cent of the corporate, made him president and signed a contract stating that if the siblings ever had a disagreement, they’d settle it on the ju-jitsu mat, with White as referee.

There are lots of sleazy jobs in Vegas but, in 2001, owning the UFC might need been essentially the most shameful. The game was advertised with the slogan “There Are No Rules”, which was true, apart from a ban on biting, eye-gouging and hitting your opponent within the balls. There have been no rounds, closing dates or judges. The one method to end a fight was knockout or give up. Fighters fought in an octagon surrounded by black, chain-link fencing. There have been no corners to flee to.

There are not any rules apart from a ban on biting, eye-gouging or hitting your opponent within the balls. The one method to end a fight is knockout

In 1996, senator John McCain, an enormous boxing fan, had railed against the UFC on the ground of the US Senate, calling it “human cockfighting”, and sent letters to the governor of each state asking them to ban the game. The American Medical Association really useful a ban as well. The UFC’s infamy was such a punchline that in a 1997 Friends episode Monica breaks up together with her millionaire tech-mogul boyfriend because he has gone insane and joined the UFC, refusing to quit even after winding up in a full-body forged. White later said in an interview at Stanford Business School: “We bought an organization that wasn’t allowed on pay-per-view. Porn is [on] pay-per-view.”

But White’s foremost problem was that nobody, not even in Vegas, would let the UFC host a fight. Until February 23 2001, when UFC 30: Battle on the Boardwalk was held on the Trump Taj Mahal in Atlantic City. Donald Trump showed up for the primary preliminary fight and stayed until the tip, many hours later. They’ve been friends ever since, and White spoke at each the 2016 and 2020 Republican conventions.

Still, by 2004, White had lost his high-school friends $34mn. As a last-ditch effort, the trio pitched a reality show based on the UFC, getting it on the fledgling Spike TV channel only by offering to finance it themselves. The Ultimate Fighter premiered in 2005. Like The Real World, the show sequestered people in a house. Unlike most episodes of The Real World, it ended with two of them fighting. Some didn’t wait until the tip of the episode. Welterweight Julian Lane would turn out to be famous in a later season for throwing a crying, wall-punching fit and yelling, “Let me bang, bro!” as housemates held him back. The ultimate episode of the primary season ended with a sanctioned fight between Forrest Griffin and Stephan Bonnar.

Because it went on, viewers called friends exhorting them to tune in, until three million people were watching.

Two years after the Griffin-Bonnar fight, the UFC had gained enough credibility for a Sports Illustrated cover line to wonder “Ultimate Fighting: Too Brutal or The Future?” In 2016, the reply was clear when talent agency and media conglomerate Endeavor bought the corporate for $4bn, netting White $360mn. The deal stipulated he keep running the corporate. White’s contract was re-upped to 2026.

Because the UFC got huge, White’s relationship together with his mother fell apart. In her book, she writes things few moms have ever said about their children, equivalent to, “Dana went from being a real friend, a superb son, and a very nice person to being a vindictive tyrant who lacks any feeling for a way he treats others.” She accuses him of cheating on his wife, accuses his wife of beating him and accuses him of beating a puppy. And of being financially ungenerous to herself and to White’s grandmother. White won’t discuss the claims.

By the point her book got here out, each Dana and his sister Kelly weren’t talking to their mom. “All of us were close. That’s the saddest a part of all of it,” Kelly says. “Dana never did anything to her. It is mindless to me. I actually have heard several things from her saying he’s very selfish. I don’t know where she gets it from or who she’s chatting with, because he gives lots to charity. I don’t know what her end game is. To not have a family?”

In that Tony-Soprano-love-your-difficult-mom sort of way, White has trouble saying anything bad about his mother. Which is telling because he doesn’t hold back on anyone else. He’s not afraid to tackle his 670 lively fighters, who’re all contract staff. A 2021 survey by sports website The Athletic showed that only 6.5 per cent of MMA fighters don’t wish to form a union. Which White shouldn’t be about to let occur. Former fighter Cung Le is an element of a potentially multibillion-dollar class-action lawsuit that’s been working its way through the legal system since 2014. It accuses the UFC of being a monopsony — a market during which there is simply one buyer — that vastly underpays its athletes. The case is more likely to reach the US Supreme Court and be the primary major monopsony ruling within the history of American law.

Whereas sports leagues equivalent to the NFL, NBA and MLB have negotiated to present half of revenues to players, the UFC probably distributes about 17.5 per cent. “Certainly one of our clients was living in a garage over his mom’s house when he was a top UFC fighter. It’s brutal,” says Eric Cramer, chair of Berger Montague, the firm representing the fighters. (Payouts to fighters range from $10,000 to $20mn per fight.) “They’re not getting medical insurance. They’re not being paid for his or her training. Their managers aren’t being paid. In boxing, it’s one promoter against one other they usually conform to fight. Within the UFC, they determine, not you, who you fight and once you fight.” Cramer claims that fighters who don’t re-up their contracts on White’s terms are scheduled to fights designed to harm their careers.

White, who hired superstar attorney David Boies’ firm to defend the UFC, dismisses every accusation. “That’s this huge paranoia with fighters, ‘You’re attempting to get me beat,’” he says. “There are not any easy fights here.” As for the fighters who took second jobs to make rent, because the lawsuit claims, White makes no apologies: “You’re either one in all the highest guys on the earth otherwise you’re not. The people in a form of lawsuit like which might be the ‘or nots’.”

The room where White and his team meet on Tuesdays to plan fights. It’s the stories behind them — veteran vs newcomer, fighters who’ve fallen out — that make UFC fights successful, says White © Holly Andres

Along with the lawsuit, White is being pressured by congressman Markwayne Mullin, who’s more likely to turn out to be a US senator next yr. The Oklahoma Republican is a former MMA fighter who turned down appearing on The Ultimate Fighter when the UFC said he couldn’t make any outside calls during six weeks of filming, not even to run his plumbing company. He’s introduced a bill that will extend the Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act to mixed martial arts. It might require an outdoor body to rank fighters, no matter whether or not they were within the UFC or one in all the much smaller MMA leagues. Top-ranked fighters would need to fight no matter which league they joined, resulting in more competition. Mullin believes that the UFC’s claim that fighters are independent contractors and never employees won’t delay in court: “I’m a plumbing contractor, so I understand these contracts slightly bit. If 100 per cent of your money is being earned by one place, you’re not a subcontractor.”

White says he’ll never let other people pick who fights, which he considers an important a part of his job. UFC commentator and former champion fighter Daniel Cormier remembers heading to a press conference right after defending the sunshine heavyweight belt in Boston, drained and bruised. “I walked to the back room and Dana leans in and says, ‘What do you concentrate on fighting Stipe Miocic in July and attempting to turn out to be a double champion? I’ll call you Monday.’” Cormier was exhausted and didn’t wish to speak about it, but White continued, offering a healthy payout. “That was essentially the most UFC way of doing things,” says Cormier. “He never stops. It’s consistently an assault on the world.”

White is so focused on arranging fights he doesn’t spend much time in his apartment-sized office. Which he can’t imagine I’ve never seen. White leads me around, playing docent in what appears to be an art gallery designed to emasculate Damien Hirst. There’s a Seventeenth-century samurai sword on the table and samurai armour within the corner. A sabre-toothed tiger skull. A Bruce Nauman painting that’s the sentence “Pay Attention Mother Fuckers” backwards. A rifle papier-mâchéd in American money with bullets stuffed with blood, heroin, gold and diamonds. An unlimited 1998 color Nobuyoshi Araki photograph of the back of a tattooed yakuza gangster having sex with a unadorned woman, titled “Tattooed Fuck”, that he got when a friend called and said he had got him a present, after which asked him to wire $200,000 for it without telling him what it was, which is a weird sort of gift, but White accepted it anyway. And when White saw it, he said, “I can’t display it! Women work here!” But then, you realize, it’s art, so he did display it, and never one person has complained.

On one other wall are two bass guitars signed by the Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist Flea which might be actually painted by Hirst, who’s, in fact, a UFC fan. Within the hallway outside, past the large pile of brass-knuckle paperweights, is a triptych of Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse preparing for and fighting within the UFC octagon.

A door in his office results in a brief hall with a full bathroom, a Kardashian-sized walk-in closet stuffed with rare sneakers and hangers with the identical T-shirt in every color, and an infinite personal gym. As he continues the tour, he makes me read all of the quotes painted on the gym wall from Bruce Lee and his good friend Mike Tyson (“Don’t be surprised if I behave like a savage. I’m a savage”). And I should totally use the gym while I’m on the town! Anytime, even the midnight when the office is closed. Before I can refuse, he has an assistant put me on an inventory to grant me complete access.

We return to the office, but only to go through on our method to one other door that results in White’s bar. Like a full-on sports bar. I would like to try Howler Head, a bourbon that tastes like banana, and White knows what I’m pondering, but it surely’s not banana in a nasty way, he guarantees. After shots of that, I would like to try Teremana, The Rock’s tequila. He had it at dinner with Dwayne Johnson in Recent York right before lockdown, and it was so good that he insisted The Rock cut him in as an investor. Johnson, excited by White’s excitement, said yeah, absolutely. “Once I went back and I opened the Teremana books, I realised that there was really nothing to present,” says Johnson concerning the day after the dinner. No problem. Totally understand. White launched his own liquor, Howler Head.

White spends most of his time across the hall from this mansion of an office, in a crappy, windowless meeting room. One wall of the room has a map of the world. One other wall has an indication that claims “Art of War” surrounded by national flags. The wall that matters is the wall with the lists. White sits here with chief business officer Hunter Campbell, senior vice-president of talent relations Sean Shelby and vice-president of talent relations Mick Maynard. And so they make fights.

Every Monday, an independent body made up of MMA media and experts sends rankings of the highest 15 fighters in each division, that are arranged on the wall. On Tuesdays at 1pm, and for the following three to 6 hours, the 4 men debate who should fight. “Crucial query is ‘What does this fight mean?’” explains Campbell. “Why should people give a shit? What’s the storyline?” Viewers wish to see an up-and-comer really tested by a veteran. Or they’ll wish to match up two guys who used to coach with the identical coach, and now one had a falling out with him. It’s not the pure, number-three-fights-number-four system that congressman Mullin wants. It’s a bit like a nonfiction version of the WWE, the massively popular American wrestling league with scripted melodrama. White insists that stories make the UFC successful.

Crucial query is ‘What does this fight mean? Why should people give a shit? What’s the storyline?’

White and Campbell then call fighters to see in the event that they’re willing, healthy and capable of come to a financial agreement. “Sometimes you’ve gotten two guys in the highest five you ought to put in a fight, but their wives are best friends. Daily, even once I’m sleeping, my phone is blowing up with fights falling apart or people wanting to fight another person. It’s fucking madness,” says Campbell.

A part of why making fights takes so long is that despite the fact that White has strong opinions, he’s a superb listener. When White stops talking for greater than a minute, his energy dissipates, and he seems to stop being attentive, possibly taking the micro-naps his body must require. But he’s absorbing information. White had long vowed to never let women fight but, after meeting with Olympic judo medallist Ronda Rousey in 2012, he modified his mind. Rousey became the highest-paid fighter on the UFC roster and a global movie star. Since women began fighting in 2013, they’ve been the highest card at greater than 40 fights. White might change his mind but, if he does, it’ll be quick. He’s the anti-Hamlet.

The last time White experienced a moment of doubt was in April 2020. He had gotten off the phone with Campbell and sat silently on the sting of his resort-sized pool, the one place he can get cell reception within the Vegas mansion he had built on the grounds of 4 multimillion-dollar homes. And he wondered if possibly he was the bad guy.

Every sport, every type of entertainment had shut down attributable to the pandemic. His bosses at Endeavor closed offices and cut staff. “I do not know what’s happening. I’m basing the entire Covid thing by what happens to Tom Hanks,” White remembers. For six long weeks, White had been stuck in his house alone. Sure, he had his wife and children. And he did throw huge pool parties, with hired bartenders. And, yes, during those six weeks he launched Howler Head. But in a way, for White, alone.

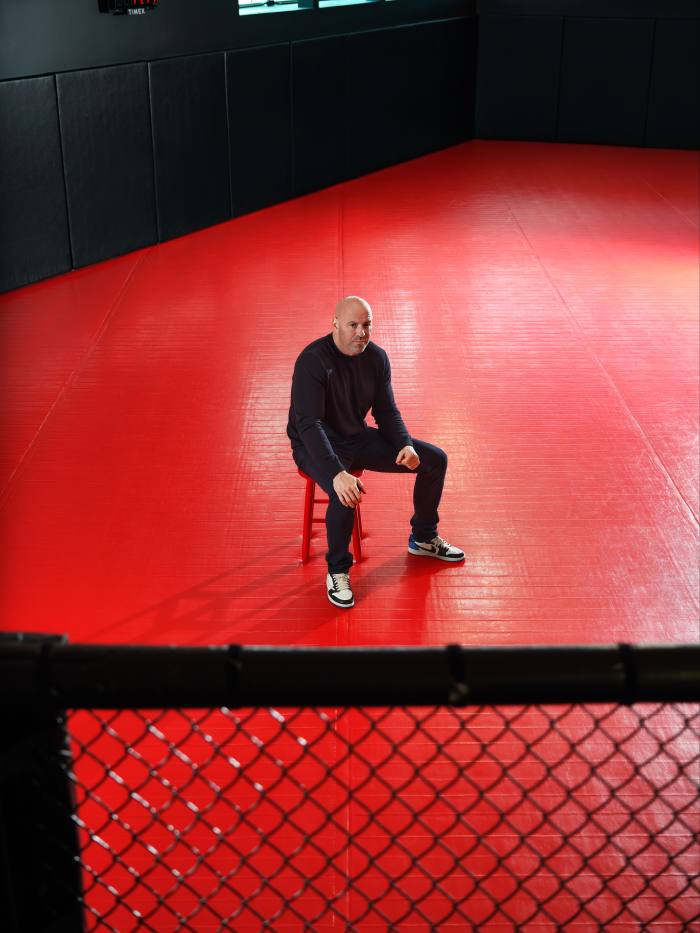

White in a training ring. The UFC chief insists that individuals will all the time stop and watch when a fight breaks out — and that admiring someone who can beat another person up is ‘built into our DNA’ © Holly Andres

Unable to take it any more, he called a gathering of his entire Vegas staff on the UFC offices, a half-hour from the eerily silent Las Vegas Strip. In person.

On the gathering of nearly 300 people, White cited one in all his company’s eight tenets: “Be first”. (There’s one for either side of the octagon.) “He said, ‘We’re going to be the leader ensuring sports paves the way in which for America leading us out of this,’” recalls Crowley Sullivan, who runs Fight Pass, the UFC’s streaming service. “The room cheered. I’ve never been in knowledgeable setting where that happened.”

Honour culture cleaves people into two tribes: your loved ones and your enemies. Loyalty to family comes first. White could be blunt, but the employees who rate UFC anonymously on the employment website Glassdoor have almost nothing bad to say. He was not going to chop salaries or lay any of his work family off. He was going to seek out a method to placed on fights. “I’m not going to grab all my shit and go hide in my big house and say, ‘Hope you’ll be able to handle your kids!’ How could I ever walk around this constructing again?” His voice cracks with emotion. “The one fucking time the shit hits the fan, I’m going to put 30 per cent of you off and cut your salaries in half?”

As a substitute, he cut a deal to provide fights on Yas Island in Abu Dhabi, an oasis for tourists that has a theme park, golf course and racing track. He renamed it Fight Island.

Many individuals thought holding an event during a pandemic was a really bad idea. The plan was thoroughly panned by mainstream media as reckless. White stared on the blue expanse of his pool: if every other company president and all those politicians and scientists and doctors and journalists were telling him he was flawed, and never just flawed, but a greedy Pied Piper leading his employees to hospital ventilators, and he had dropped out of two colleges after one semester each, what did he really know? Might he be flawed? Might he be a monster?

The moment lasted “like a second. After which I used to be like, ‘Yeah, no, we’re going,’” White says. On the UFC, it’s Fuck It Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday.

The fear that gripped the US, he says, made him worry greater than the virus. “I felt America getting soft for the last 15 years. This can be a very scary fucking place straight away with how soft we’re,” he says. White never wore a mask, and he made sure that nobody, including me, wore one around him. “You understand why I got vaccinated? That lunatic” — he’s referring to Endeavor CEO Ari Emanuel — “called me 357 times a day telling me to get vaccinated. I wasn’t into it, but I did it. I used to be one in all the primary.” Emanuel, a supporter of liberal causes, gets along well with White, who, despite his love of Trump, is a pacifist atheist whose voting record mostly hinges on who was most antiwar on the time: Bush, Kerry, Obama, Romney after which Trump twice.

White is sitting within the green room after the Volkanovski-Ortega weigh-in, folded right into a chair even larger than he’s. He leaves a voicemail for Halle Berry, who starred in and directed the Netflix movie Bruised, a couple of mixed martial artist. She was imagined to have dinner with the winner of a charity raffle but can’t make it. So White decides to take them himself.

Trophies lined up in White’s office. White first met real fighters as an apprentice boxing trainer in Boston, and quickly realised he wasn’t one in all them. He’s a jock, he says — and never even a troublesome one © Holly Andres

As he’s establishing reservations, two women enter. White excitedly shakes hands with Nour al-Harmoodi and Noura Kahil, who each work for Abu Dhabi’s department of culture and tourism. White immediately apologises for touching them. Kahil, who’s wearing a hijab, waves off the protest. “We’re not in Abu Dhabi,” she says, laughing. They’ve met White repeatedly and find the whole lot he says hilarious, only partly because the whole lot is either a compliment about them or their country. After they leave, White has his assistant make them a reservation at Carbone, the Vegas outpost of the retro Recent York Italian joint where Sinatra blares from speakers and the rigatoni alla vodka costs $32, going through the menu to order his favourite dishes and pay for a meal there’s no way two human beings can eat.

The deal to create Fight Island wasn’t the primary time the UFC partnered with questionable money. In 2018, Russia’s sovereign wealth fund invested within the creation of a UFC offshoot within the country, and White continues to book fighters affiliated with Chechen dictator Ramzan Kadyrov’s Akhmat MMA fight club despite the gym and its affiliates being sanctioned by the US Department of the Treasury.

But White’s love for Abu Dhabi is longstanding. And peculiar. It stems from the proven fact that crown prince Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed al-Nahyan is actually into Brazilian ju-jitsu. Many children study it in class as a part of the curriculum. The country holds numerous the game’s biggest tournaments and owned 10 per cent of the UFC before the Endeavor buyout.

I felt America getting soft for the past 15 years. This can be a very scary fucking place straight away with how soft we’re

The sheikh once took White hunting, though White bailed after shooting a bird. “It’s a horrifying experience. I killed a duck. That’s not right. It was flying around and having a superb time and now it’s not — attributable to me? Fuck that,” he says. “Hunters are pussies. What’s a deer going to do to you?”

His attitude toward hunting didn’t hurt their relationship. Neither did the UFC’s insistence that fights held within the country include scantily clad ring card girls and openly lesbian fighters. White applied to be one in all the 400 or so people, including Cristiano Ronaldo and Novak Djokovic, granted “golden visas” to the United Arab Emirates, and the connection between the UFC and the UAE is stronger now than before the pandemic. Fight Island isn’t going away.

The Volkanovski-Ortega fight is my first since I used to be a sports author in 1996 and saw Andrew Golota disqualified for hitting Riddick Bowe below the belt at Madison Square Garden. The incident led to a riot in the sector that sent 12 fans to the hospitals and resulted in 11 arrests. I swore I’d never go to a fight again.

People still dress up for fights. Sure, half of the 19,000 fans on the T-Mobile Arena are in T-shirts and jeans, but lots are here on a Saturday night date, dressed like they’re auditioning to affix the Rat Pack. Even White, whose business uniform is a T-shirt and jeans, suits up. He doesn’t sit within the front row with the odd assortment of outlaw celebrities: Mel Gibson and the Nelk Boys, Canadian YouTube pranksters that so amused White he took them aboard Air Force One to satisfy Trump. As a substitute, he, Campbell and Epstein sit at a table with the judges.

The fights start at 3pm, and a surprising number of individuals show up for all of them. I’m within the press seats ringside and, to my relief, despite the kicking, the submission holds, the fingerless gloves that end in more cuts and blood, the fights are not any more violent than a boxing match. If anything, they’re more tactical since the fighters have so many more options. Still, each time anything happens apart from face punching, the group boos. Spectators are most satisfied with the ground-and-pound, when a fighter sits on top of their prone opponent and swings at their face with fists and elbows. The group is so enthusiastic that when combatant Jalin Turner triumphantly tosses his mouthguard into the stands, the lucky fan who scoops up the wet trophy high-fives his friend as if Covid didn’t exist.

The penultimate match is between flyweight challenger Lauren Murphy, a single-mom high-school dropout from Alaska who struggled with drug abuse, and Valentina Shevchenko, who’s from Kyrgyzstan but lives in Peru, speaks five languages, offers respect for opponents like a Zen master, won the Peruvian version of Dancing with the Stars and acts in Berry’s film. White says fans won’t accept a card without women fighting, and that is the second one in all the night. His problem, he says, is he can’t find the feminine talent to satisfy demand.

Lauren Murphy (left) and Valentina Shevchenko fighting in Vegas last September. White modified his mind on women featuring within the UFC after meeting the Olympic judo medallist Ronda Rousey in 2012 © Alex Bierens de Haan/Getty Images

The story of the ultimate fight of the night, between Volkanovski and Ortega, is about how much they hated one another on The Ultimate Fighter. And it shows. Ortega gets punched so often his face becomes a Halloween mask of blood. He’s so woozy and weak that, in between rounds, the ref asks Ortega what number of fingers he’s holding up, though the fans scream out the reply to make certain. the fight keeps going. This is the reason I stayed away from combat sports for 25 years.

Within the third round, though, Ortega can see enough through his bloated face to jab Volkanovski in the top, sending him to the bottom long enough for Ortega to place him in a choke hold. Because the blood flow from Volkanovski’s carotid artery is cut off and his brain is deprived of oxygen — just as mine had been when White made me experience this years ago — the group cheers. As Volkanovski starts to lose consciousness, he by some means wiggles out and gets on top of Ortega. He grounds and kilos, improbably finding more places on Ortega’s face that aren’t yet bleeding to bust open.

Although I’m on the opposite side of the ring from White, I need to still be under his influence. Because while intellectually disgusted, I find the fight compelling.

Ortega, who can barely see as he lies there below Volkanovski, kicks up his legs, wraps them around Volkanovski’s neck and clamps down. It looks prefer it’s throughout for Volkanovski, and the group can’t imagine it. But again, Volkanovski slips out. When Ortega gets Volkanovski in one other match-ending choke hold in the next round, Volkanovski gives the referee a cocky thumbs-up and gets away again. After five rounds of 5 minutes each, the judges give Volkanovski the unanimous victory. Most league commissioners could be professionally neutral. White celebrates wildly.

I can’t place two of the blokes White’s sitting with. I’ve talked to everyone high-up on the UFC, yet they don’t look familiar. It seems they’re the charity auction winners who were imagined to have dinner with Halle Berry. “I expected Dana White to say ‘I’ll have one drink and dinner is on me’, and leave,” says Dan Zampella, a Recent Jersey insurance underwriter who’d spent $30 on raffle tickets. “As soon as he saw me, he said, ‘I’m going to be out with you guys all night tonight.’”

White likes to gamble. But not in the way in which that almost all people do. “I’m not going there to hang around and have some drinks. I’m getting in with a plan to cripple that place,” he says. White often plays blackjack in a personal room arrange within the Mandalay Bay, where he blasts his own music and orders food from the restaurants on the hotel. Mandalay gave him a $75,000 limit to lure him from Caesars Palace, which only let him bet $50,000 a hand. He’s pretty sure that $75,000 — which he doubles by playing two hands at a time — is the best limit anyone has in Vegas. “I’d bet 1,000,000 a hand in the event that they let me. All these casinos now are run by bean counters,” he says. “Vegas is nothing prefer it was once.”

Beneficial

White doesn’t count cards. “I can barely count to 21 on my fingers and toes,” he says. But because an enormous loss can hurt a casino’s bottom line, White has been banned from several after winning big. Not way back, on the Mandalay Bay, he got a hand he was capable of split five times and double-down on all of them, allowing him to win $750,000 on a single hand. “I’ve never done heroin. I’ve never snorted cocaine. But that’s what it appears like when the cards began flipping,” he says. “I give most of it away. I tip the shit out of everybody. It’s not like I’m buying mutual funds with it.” And he doesn’t share the stories together with his family. “What they don’t know won’t hurt them. My wife won’t be reading this.”

White brought Zampella and his friend, together with a small entourage, to dinner at Prime Steakhouse on the Bellagio. When Zampella mentioned he’d lost $100 gambling there earlier, White dragged him back to the tables. However the Bellagio informed White it wouldn’t deal cards to people with no mask, so White got his driver to take all of them downtown to the D Casino & Hotel. “He coached me through it and I won $1,000,” Zampella says, though he doesn’t know the way much White won. “I used to be a nervous wreck since it was lots.”

At 2.30am, Zampella’s friend, jet-lagged, insisted they leave White on the tables and return to their hotel. White’s enthusiasm had momentarily failed him. As White is telling me about his gambling wins, I let it slip that I don’t like blackjack. Upon hearing this, he makes me promise that next time I’m in Vegas, I’ll go along with him to the Mandalay Bay to play with him all night. And by some means, despite the fact that none of that seems interesting to me, I can’t wait to do it.

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to seek out out about our latest stories first